- Published on ·

- Reading time 6 min read

Understanding NPM Dependencies While Creating a Distributable Package

A step-by-step guide to solving a problem

Share this page

Introduction

I recently had to develop a distributable NPM package that depended on a third-party package. This distributable package, other than providing useful functionality, also exported an interface that combined properties from itself and the third-party package. However, when I tried using my NPM package from the consumer application, I encountered an error informing me that the properties from the third-party package didn't exist. In this article, I'll aim to recreate the problem and take you on this journey to what the solution is.

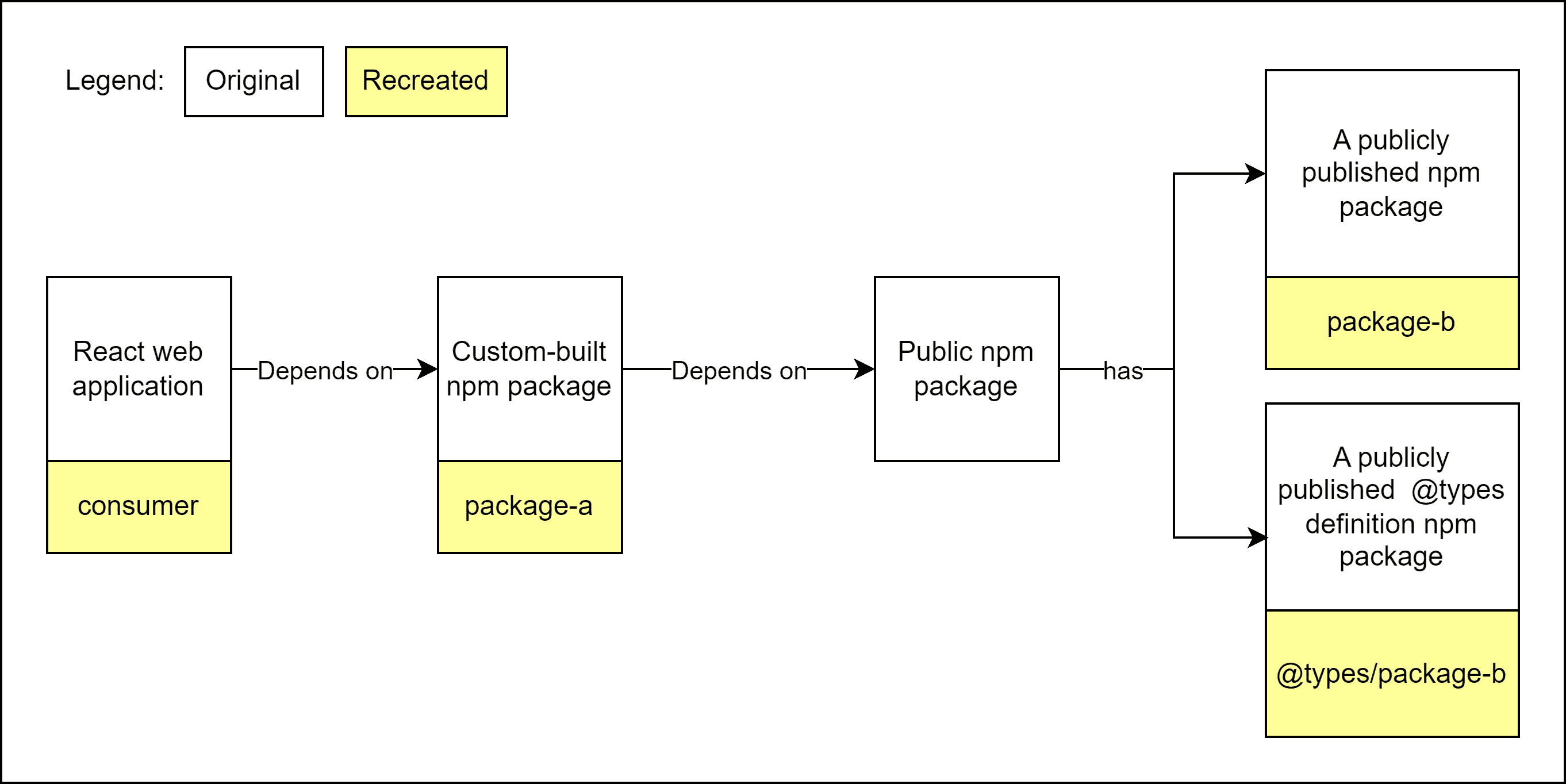

Throughout this article, I've recreated the required npm packages enough to be able to demonstrate the problem and solution. A visual representation of the recreated artifacts and what originals they map to is illustrated in the diagram below, for your reference.

Image courtesy of the author

Part 1: The distributable package-a

Let's say we're working on creating a distributable package called package-a. From this package, we'll export an interface that will have one property from package-a and one property from package-b by extending the interface from package-b. The code snippet below shows what it would look like in action.

import { IPackageB } from 'package-b'

export interface IPackageA extends IPackageB {

propertyOne: string

}

export const sayHello = (props: IPackageA) => {

// props.propertyOne from package-a

// props.propertyTwo from package-b

console.log('hello from package a', props.propertyOne, props.propertyTwo)

}

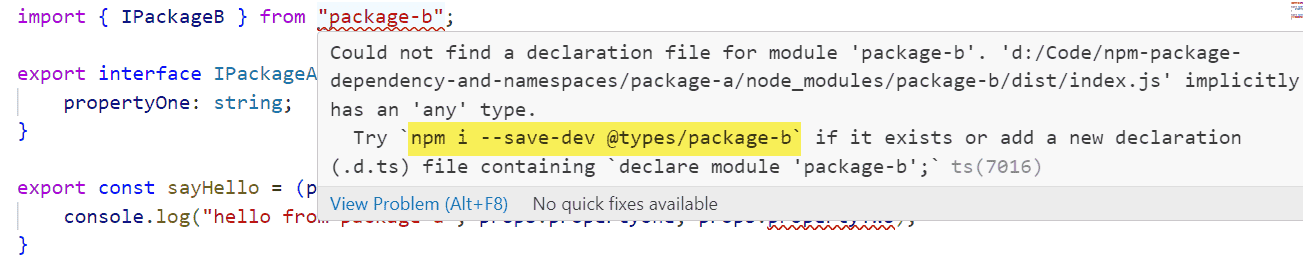

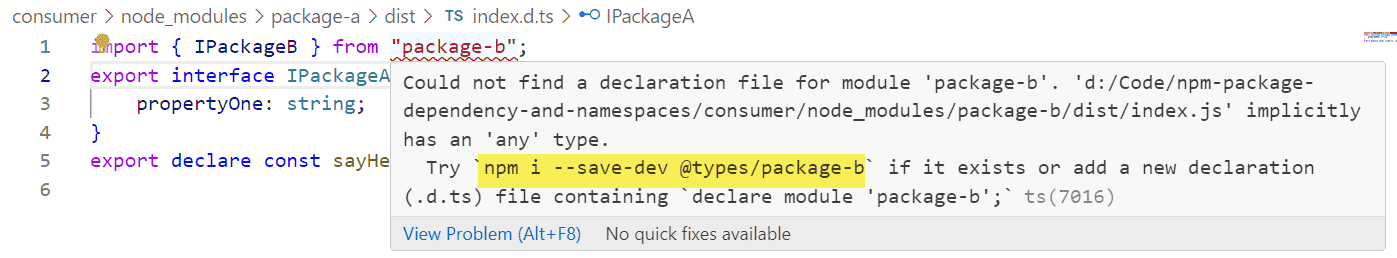

However, we seem to be getting a compile-time error because the project cannot find a declaration file for module package-b.

Image courtesy of the author

Let's follow the suggested solution to run the npm i --save-dev @types/package-b command. Doing so resolves the error. But how did that resolve it?

Part 2: Unboxing package-b

To answer that question, let's take a look at how package-b was made and published.

This package has an exported interface with a property in it, like the code snippet below. So, we can be assured that it does export what we need.

export interface IPackageB {

propertyTwo: string

}

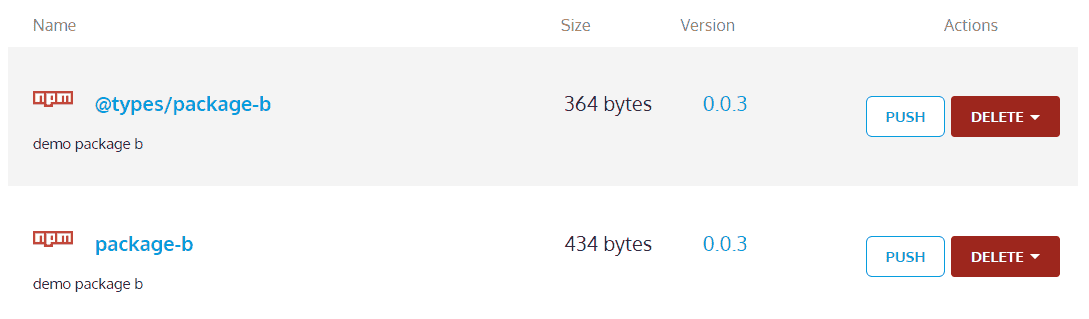

In terms of how it is published, aside from the primary package-b, this package-b has the types file published as a separate package prefixed with the scope @types. Since this is a recreation, I've tried to emulate how the external dependency was published in the real scenario. This setup is quite common. For example, jQuery's package can be found on npm js, but if you're using TypeScript, then you'd also want to install the @types package which contains the TypeScript declaration file.

Image courtesy of the author

Looping back to the error we encountered in the earlier section, since package-a was written using TypeScript, just installing the primary package wasn't enough. We also needed the TypeScript definitions for package-b to be included which was done by installing the @types/package-b package using the npm i --save-dev @types/package-b command.

Part 3: The downstream consumer

Great, so our distributable package package-a is ready. We've published package-a to our npm feed and it's now ready to be consumed. The steps to publish an npm package are out of the scope of this article, so I'll skip documenting that here.

Our consumer application is a simple TypeScript script that when compiled into JavaScript, we can run it using the command line to test out our package. Since this is a recreation, I'm keeping the consumer application lightweight, but in the real scenario, it was a full-blown web application.

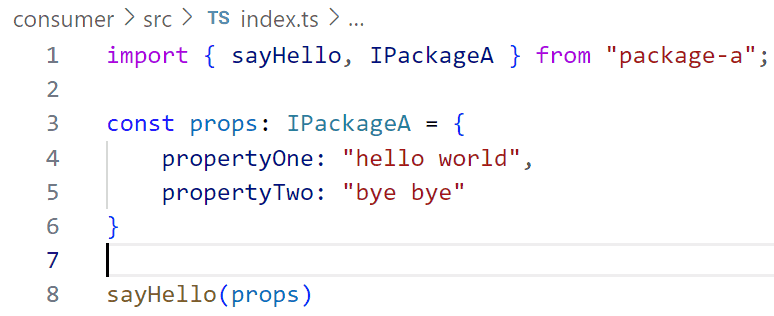

We'll install package-a into the consumer application and then write a block of code, like the snippet below, to test out package-a.

import { sayHello, IPackageA } from 'package-a'

const props: IPackageA = {

propertyOne: 'hello world',

propertyTwo: 'bye bye',

}

sayHello(props)

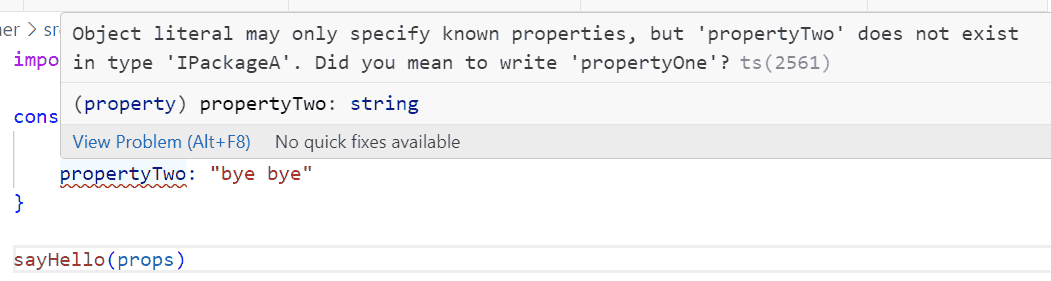

But wait, what's this? When consumed, propertyTwo which was the one extended from package-b, isn't recognized.

Image courtesy of the author

In VS Code, if I click on the IPackageA interface, I can peek into package-a's code that's located in the node_modules folder and we see an error again. This seems to be the same error we encountered earlier along with the same suggested solution. But when we fixed this issue while developing package-a, why is this complaining again?

Image courtesy of the author

Part 4: The type of dependency

If you recall, in the first section, we followed the suggested solution to run the npm i --save-dev @types/package-b command. This places the types package @types/package-b in the devDependencies section of the package.json file while the primary package-b remains in the dependencies section. Below is the code snippet from the package.json file of package-a.

"devDependencies": {

"@types/package-b": "^0.0.3",

"typescript": "^5.3.3"

},

"dependencies": {

"package-b": "^0.0.3"

}

While running the aforementioned command resolves the error while developing package-a, packages added to the devDependencies section don't get bundled along when package-a is published. As per this npm js article, devDependencies are for packages that are only needed for local development and testing. This meant that the @types package never got bundled when we published package-a, and since package-a required that as a dependency but couldn't find it, it errored out.

To resolve this, we'll move @types/package-b to the dependencies section in the package.json file for package-a, run npm install again, and publish an updated version of package-a upstream. This is what the package.json file of package-a would like now.

"devDependencies": {

"typescript": "^5.3.3"

},

"dependencies": {

"package-b": "^0.0.3",

"@types/package-b": "^0.0.3",

}

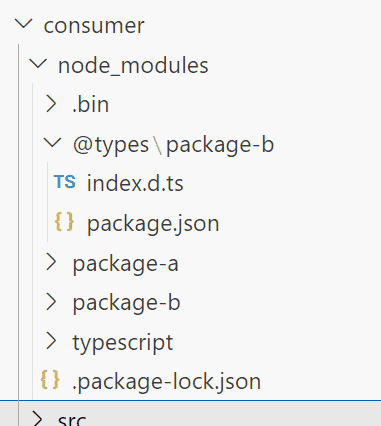

Now, when our consumer application installs the latest version of package-a, you'll notice that the error has gone away.

Image courtesy of the author

And if you peek into what node_modules have been installed in the consumer application, you'll notice that the dependent types package @types/package-b now exists.

Image courtesy of the author

Until this point, I hadn't really paid attention to how a tiny decision of choosing the type of dependency has a trickle-down effect on its consumers, but this was a good learning experience for me. I hope you've learned something, too.

That's it! Thanks for reading.